<aside> <img src="/icons/home_gray.svg" alt="/icons/home_gray.svg" width="40px" />

</aside>

<aside> <img src="/icons/send_gray.svg" alt="/icons/send_gray.svg" width="40px" />

</aside>

Getting Started (SolidWorks Plugin)

Documentation

GD&T

Learn more about GD&T tips and tricks

<aside> <img src="/icons/thought_gray.svg" alt="/icons/thought_gray.svg" width="40px" />

</aside>

For further support, contact your Drafter support representative

<aside>

</aside>

<aside>

</aside>

Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) is a symbolic language used in engineering drawings to define the allowable variations in the geometry of parts and assemblies. GD&T standardizes communication of functional requirements, ensuring parts are manufactured, fit, and function correctly within acceptable limits of your Design Intent.

In today's globalized and competitive manufacturing environment, the ability to produce high-quality parts efficiently and consistently is more important than ever. GD&T plays a crucial role in this by providing a standardized way to communicate design intent. Whether you're working on a simple part or a complex assembly, GD&T ensures that every detail of your design can be clearly understood by everyone involved in the production process.

<aside>

A basic GD&T part drawing

</aside>

Design intent refers to the purpose and functional requirements that a designer aims to achieve in a product or part. It encompasses the desired performance, aesthetics, manufacturability, and usability of the design, guiding decisions throughout the development process to ensure that the final product meets its intended goals. Design intent also ensures that all design elements work together cohesively and that any variations in manufacturing still result in a functional and acceptable product.

In 1990, NASA launched the Hubble Space Telescope, a marvel of engineering that promised to give us crystal-clear images of the universe. But when it started sending back photos, there was a big problem—the images were blurry. This wasn’t just a slight blur; they were completely unusable, causing an uproar after years of work and billions of dollars spent.

So what went wrong? The culprit: a tiny manufacturing error in the telescope’s main mirror. It was off by just 2 microns—that’s 1/50th the thickness of a human hair. While that sounds ridiculously small, in the world of high-precision optics, it was a disaster. The mirror wasn’t positioned exactly as it should’ve been because the tolerances for how it needed to be manufactured and assembled weren’t properly followed.

In engineering terms, the GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing) was off. The features of the mirror weren’t controlled correctly, and that tiny misalignment ended up ruining the functionality of the entire telescope. The result? NASA had to spend millions more dollars and launch a whole new mission just to fix the problem by installing corrective optics.

Thankfully, after the repair, Hubble went on to become one of the most successful space telescopes ever. But this story is a perfect reminder of how crucial GD&T is in engineering. Even the smallest mistake in how we control and define tolerances can lead to major setbacks, extra costs, and delays. It’s not just about designing parts; it’s about ensuring those parts work together exactly as intended.

GD&T is more than just a set of symbols and rules—it's a powerful tool for ensuring that your designs are manufactured correctly, function as intended, and can be produced at scale. By using GD&T, engineers can communicate their design intent more effectively, leading to better products, fewer production issues, and lower costs. Just remember: a few microns almost doomed one of the most important scientific tools in history.

Every assembly is made up of different parts that work together to serve a specific purpose. As an engineer or manufacturing professional, your goal is to design a system of parts that best achieves this purpose, meets all the design requirements, and does so at the lowest possible cost. The cost is directly tied to how easy the parts are to manufacture and how scalable the production is. This depends on factors like the material used, the process to make it, and the time it takes to produce.

There are two main areas you can adjust to control costs: your design requirements (which influence things like material choice and how strong the parts need to be) and the shape of the parts (geometry). Since each part is made of material and has specific features, these features either serve a function or help the part connect with other components. To ensure the part meets your design goals, engineers use something called GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing) to carefully define the size, location, orientation and form of these features.

The four categories of control in GD&T follow the SLOF framework:

Each category plays a key role in making sure parts fit together and function as designed, even with real-world imperfections.

<aside>

</aside>

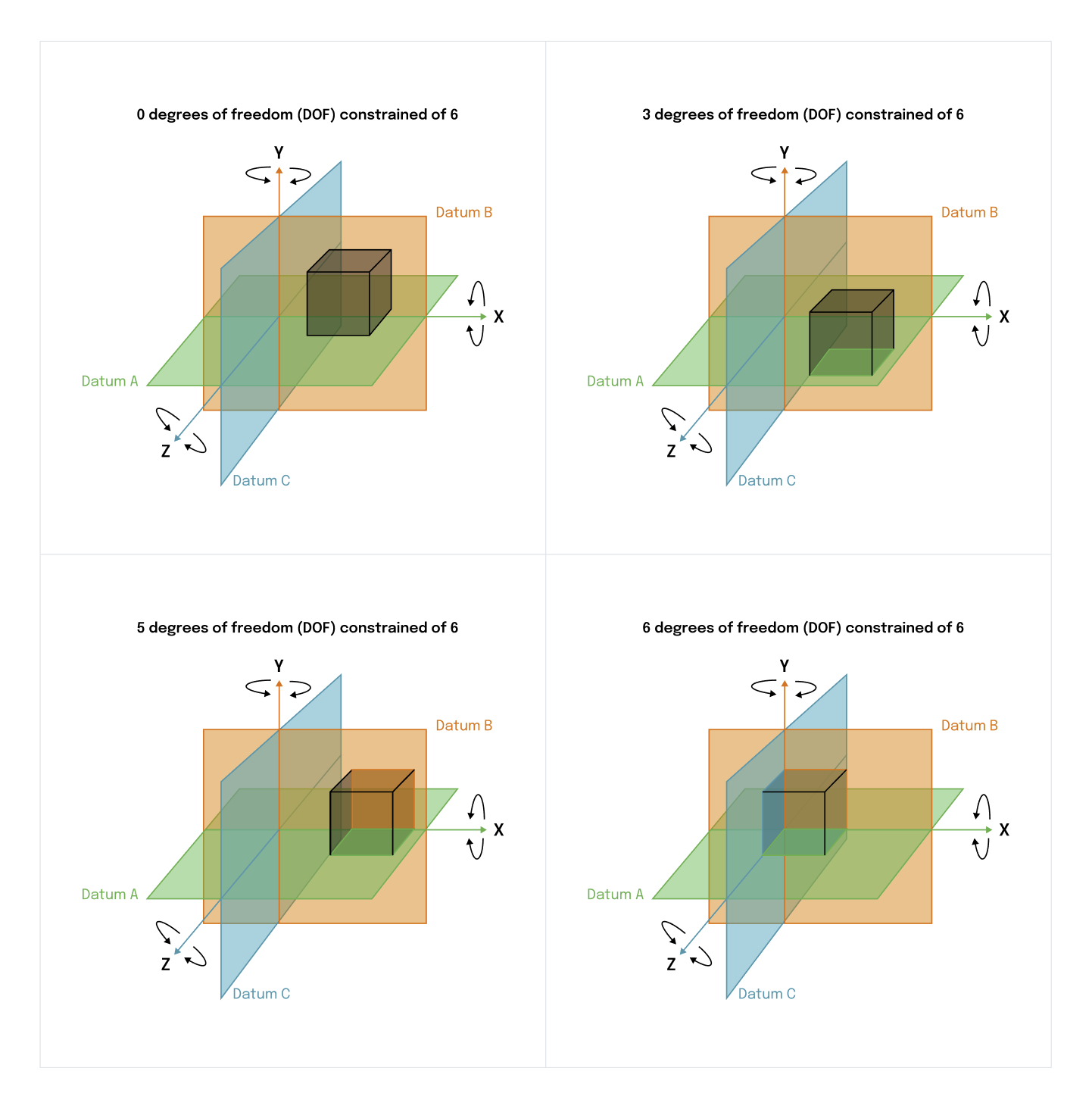

Before diving into reading GD&T symbols, you must understand datums. A Datum Reference Frame (DRF) serves as the reference point for all measurements. It’s essentially a coordinate system that allows the engineer to control the orientation, position, and size of a part.

A DRF is made up of multiple reference surfaces or features, usually marked by letters (A, B, C). These letters correspond to features on the part, such as flat faces, and help define how the part is constrained.

Example of planar datums:

<aside>

How datum assignment constrains degrees of freedom

</aside>

We’ll go into more detail later about how to select "datums," but for now, here’s a brief overview of some basic rules:

The best GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing) is based on the part's function, so a good Datum Reference Frame (DRF) is often guided by how the part is mounted. This creates what’s called the Mounting Datum Reference Frame (MDRF).

When selecting datums, start by choosing surfaces or features that have the largest surface area because they help to "constrain" the part in space. Constraints refer to how a part is held or restricted in movement during assembly and use. Think about how the part will be put together and how it needs to stay in place during its operation.

Each datum helps lock the part in place during assembly and ensures it functions properly.

Comments:

Now we’re getting to the core of reading and writing GD&T—the Feature Control Frame (FCF). The FCF is the box on a drawing that contains all the necessary information for controlling the feature.

Each FCF contains: